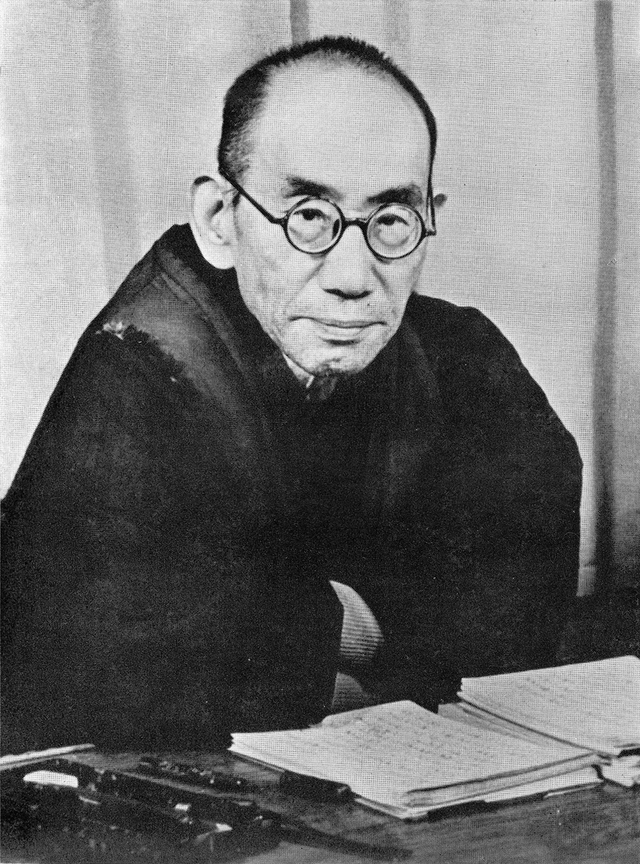

Nishida Kitarō (1870-1945) is still a little-known author to the Brazilian audience. In fact, it must be said that we have little or no contact with Japanese philosophy, especially when compared to European or American philosophy.

This may be partially due to the young age of this academic field in Japan. Until the Meiji Era (1868-1912), the word “tetsugaku” (哲学) did not exist, being one of the neologisms created within the nationalist program to internationalize Japanese society and culture. Among the many chaotic and rapid transformations, one of them was the introduction of a scientific-philosophical thought, and Nishida Kitarō belongs to the pioneering generation that first attempted to formulate a philosophy suitable for local history rather than a mere application of European authors.

Nishida had a tumultuous journey, filled with tragedies, deaths, and disappointments. His philosophical trace reflects part of this hardship, supported also by his Zen Buddhist practice, which accompanied him during the most challenging moments of life.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1911, he gained recognition for his first significant work. Zen no kenkyū (善の研究, translated in English as “An Inquiry into the Good”) brought a revision of William James’s concept of pure experience, appropriated and reinterpreted by Nishida as something closer to everyday life and achievable through incessant practice.

But this time, I would like to talk about a short essay released eleven years earlier, in 1900, titled Bi no Setsumei (美の説明, lit. “Explanation of Beauty”). Although its brevity might seem to make it simple, Nishida objectively and subtly discusses what he understands to be beauty and how we are capable of apprehending it.

What is Beauty?

The first sentence of the text already poses to the reader a question that perhaps constitutes the most primordial basis of Aesthetics, a branch of Philosophy concerned with answering not only this question but many others as well. Nishida comments that beauty has long been considered a type of pleasure (快楽 kairaku), albeit this being only a partial truth, as we do not consider drinks or food aesthetic pleasures, for example. Something can be pleasurable and not necessarily aesthetic.

By quoting Henry Rutgers Marshall, he adds the argument that aesthetic pleasure must be a stable pleasure, that is, “not limited only to the moment it is felt but enjoyed in the same way when recalled later” (p. 215).

However, Nishida is not satisfied with this explanation. This is because it is still necessary to understand what the special characteristic of the sense of beauty is. According to Kant, as cited by the Japanese author, “the sense of beauty is pleasure dissociated from an ego, it is ‘the pleasure of the moment when one forgets one’s own interest such as advantages and disadvantages, losses and gains’” (p. 216).

Indeed, Kantian theory claimed that aesthetic judgment is devoid of interest, allowing free play between faculties (knowing, judging, desiring). Nishida’s critique of Kant lies in the rational aspect, as, for Kant, aesthetic judgments are capable of producing knowledge, and thus, Man should constantly refine his sensibility, as he would simultaneously be improving his reason.

Beyond dualities

Kantian thought presupposes a necessarily dualistic epistemology, where subject (the one who sees) and object (the one that is seen) are separate. There is a being capable of knowing what is there to be known. Nishida claims that beauty is equivalent to truth and, from this perspective, it cannot be accessed through intellectual truth (論理的な真理 ronriteki na shinri), but only through intuitive truth (直覚的な真理 chokkakuteki na shinri).

In other words, it is a critique of the idea that logic would be supreme to intuition, an element that constitutes, in Nishida, one of the pillars. In his later key concepts, such as basho (場所) and zettai mu (絶対無), the importance of intuition is notable, as it is achieved “when we separate from the self and become one with things” (p. 217), a state called muga (無我). Borrowed from Buddhism, muga is the condition of non-self (anātman in Sanskrit), that is, the perception that there is no fixed or independent self, but rather exists in a complex network of causality.

The state of muga and the intuitive truth derived from it are capable of “penetrating the deep secrets of the universe,” hence, “the beauty that evokes this feeling of muga is the intuitive truth that transcends intellectual discrimination” (p. 217). Beauty is, therefore, the feeling of muga.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

We appreciate beauty from the moment we unite with the object, transcending dichotomies and dualities. In the face of beauty, we are transported by intuitive truth to a state of simple and pure contemplation of things as they are, what Nishida calls “the truth seen with the eyes of God.” But this feeling is only momentary; the muga of beauty is fleeting, as there exists an eternal muga considered: that of religion. Nishida believes that the muga of beauty and that of religion share the same nature, differing only in their durability. Similarly, morality is also grounded in the same roots, namely, the self-abnegation, even though it belongs more to the world of discrimination, as the idea of obligation is intimately linked to the distinction between self and other, between good and evil.

But by diligently practicing morality, it is possible to undo these separations, as morality and religion become indistinguishable, manifestations of muga as much as beauty.

Muga is, therefore, one of the innovative concepts that Nishida Kitarō brings to Aesthetics, even though he never elaborated a specific aesthetic theory. Nevertheless, we can infer that the absence of muga is an impediment to the contemplation of the beautiful. Without disconnecting from the idea of a fixed and independent self, we will never be able to know true beauty, as we will always be subordinate to intellect and reason. Indeed, the distancing from nature and the loss of religiosity are symptoms of a weakening in the ability to recognize and appreciate beauty, consequences of a modernity in which humans believe they can understand the world only through words and logical thought.

References

ODIN, Steve; NISHIDA Kitarō. “An Explanation of Beauty. Nishida Kitarō’s Bi No Setsumei.” Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 42, n. 2, 1987, pp. 211–217. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2384952.

Leave a Reply